The term “Latin America” originated in the 19th century, primarily as a geopolitical construct to distinguish the nations of the American continent that spoke Romance languages from those within the Anglo-American sphere. It was precisely French intellectuals and political strategists who popularised the term, with the aim of emphasising the linguistic and cultural ties between France and the former Spanish and Portuguese territories.

However, the term carries an ideological weight, as it implicitly minimises the Spanish and Portuguese legacy by grouping the region under a broader “Latin” identity that includes non-Iberian influences. Moreover, the term Latin America was explicitly designed to undermine the authority and prominence of Spain in the discovery and construction of the New World. This intention was promoted by France and reinforced by the United Kingdom.

Defining the concept of Latin America is highly controversial and complex. Despite its widespread use today, significant difficulties arise when reflecting on the term as a concept, along with its meaning and importance. Today, what is commonly known as Latin America—or Latin America and the Caribbean—is a compound noun referring to the part of the American continent that extends from Tierra del Fuego (Chile and Argentina) in the south to the Rio Grande on the border between Mexico and the United States. It includes the Caribbean islands and the southern and central regions of the continent. Politically and socially, it refers to the countries of the continent that differ from what is known as North America—excluding Mexico. Linguistically, it refers to the group of countries where a Latin or Romance language is spoken, in this case Spanish or Portuguese.

Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, the term “Latin America” signifies this and much more. It is the result of very complex and long-standing socio-political-economic-geographical-cultural contexts and situations, to quote Fernand Braudel. At least, the idea and concept of “Latin America” were shaped both despite and thanks to North American expansionism; and it was also a project to create an empire on American soil promoted and supported by France and Napoleon III.

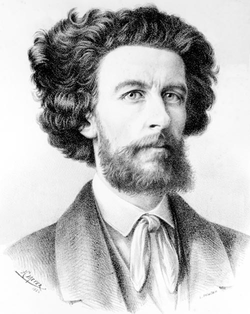

The ideologues of Napoleon III, and more specifically Michel Chevalier, are considered the creators and architects of the concept of Latin America. Chevalier is cited for his book Des intérêts matériels en France (1838), where he emphasises the importance of establishing a “Latin America” as a counterweight to the previously more accepted and widespread term “Hispanic America” or “Spanish America,” used from the beginning of the colonisation of the New World until almost the end of the 19th century and even into the 20th century. This was a novelty even in France, where until the 1910s newspapers and books constantly referred to les pays hispano-américains, les hispano-américains, or l’Amérique espagnole.

In fact, Chevalier first used the term Latin America in 1836, in the introduction to Lettres sur l’Amérique du Nord. In this text, the author began to outline his idea of “Latin America.” Yet, it was not until Des intérêts matériels en France that a more developed concept emerged. In this work, Chevalier argues that modern “Civilisation” has a dual root, both complementary and contradictory: the Roman tradition and the Germanic tradition. Thus, the future of society and “Civilisation” was once again at stake, now in a new space called “America,” where both traditions coexist and clash once more. For Chevalier, the American continent harbours two “civilisations” or cultures, complementary but opposed. One is Saxon and Protestant: industrious, white, attached to and respectful of the institutions it creates, but discriminatory, disdainful of difference, driven by a clear manifest destiny. The other America is Latin, Catholic, mestizo, both European and “barbarian,” with little recognition or respect for the institutions in formation, but unafraid of the other, eager to encounter, confront, teach, and learn. This reflects a highly romanticised view of Latinity compared with a highly pragmatic view of the Saxon world.

In addition to Chevalier, a merchant and author named Benjamin Poucel reflected around 1850 on the idea of Latin America in two of his works: On European Migrations to South America and Studies of the Reciprocal Interests of Europe and America, France and South America. Poucel called for France to establish a more substantial presence in the Americas and counter the growing influence of the United States over the emerging nations of the continent. To this end, he invoked the idea of Latinity, attempting to show that the southern nations of the continent had far more in common with France than with the United States.

Alongside these two French authors, several American writers also engaged with the concept of Latin America. Among them were the Dominican Francisco Muñoz del Monte and the Colombian José María Torres Caicedo; the latter is often considered the first Hispano-American with a historical consciousness of Latin thought.

The Chilean Francisco Bilbao also contributed to this trajectory. In 1856, following Torres Caicedo, Bilbao published a poem entitled The Two Americas, in which he clearly and unequivocally distinguishes between two Americas: one Saxon and one Latin.

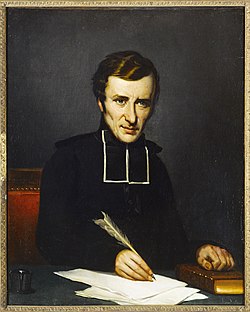

Bilbao’s work reflects the influence of another French thinker, the Abbot Félicité de Lamennais, who also explored the idea of Pan-Latinism from a European perspective, under different circumstances and logics.

In a lecture delivered in Paris in 1856 entitled Initiative of the Americas: Idea of a Federal Congress of Republics, Bilbao articulated the dominant vision among Hispanic American elites: the existence of two races, two cultures, and two civilisations, each seeking to dominate the world in its own way. One represented the Saxon/materialist culture, while the other symbolised the Latin and more spiritual culture.

From 1860 onwards—and practically until today—the term Latin America has been regarded as a French invention, created and promoted by the imperialist ideologues of Napoleon III to justify their interest in establishing an empire on Mexican soil. As already mentioned, the use of Latin America sought to erase or diminish the idea of a “Hispanic America” or “Spanish America,” offering a common identity that had no strong ties either to the former colonial power or to the new northern giant. This also explains why terms such as “Ibero-America” and “Hispano-America” remain common in Spain, as well as the reluctance of Latin American countries to refer to the United States simply as “America,” as is often done in the U.S.

Due to the rapid and tumultuous political and social events from the 1860s onwards in the Americas, two terms gained prominence. The English term “America” came to refer to the Saxon tradition and the regions of the continent under that influence, while “Latin America” described the parts of the continent outside the Saxon world.

The Case of Hispanic America or Hispano-America

The term “Hispanic America” is more culturally and historically accurate than Latin America to describe that part of the world, as it emphasises the shared Spanish heritage of the region. It reflects the centrality of the Spanish language, Catholic traditions, and cultural values brought by Spain during the colonial period. This terminology reaffirms the unity of nations bound by a common history and linguistic identity, while avoiding the broader and often diluted connotations of the term Latin America.

Spain transplanted its entire civilisation to these countries without any external assistance. Once grown and mature, these Hispanic countries followed the example of the United States and separated from their Motherland, Spain, naturally preserving their language, laws, customs, and traditions, as they had done previously. They also imitated the United States in this regard, preserving their native English language, the Common Law, and English laws, customs, and traditions, despite the diversity and large number of immigrants admitted.

In addition to most of the countries in the region, which are Spanish-speaking republics, there is Brazil, created by Portugal, where Portuguese is spoken and Portuguese laws, customs, and traditions prevail. However, this country is also Hispanic, because Hispania, like Iberia, included both Portugal and Spain. Therefore, the term Hispanic America encompasses all that derives from Portugal and Spain. The name of the Hispanic Society of America in New York, founded in 1904 to study American history linked to Spain and Portugal, is no coincidence. It was chosen over Latin Society of America, as the latter would have been misleading, false, and grossly erroneous, just as applying the term “Latin” to Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking nations that do not descend from France or Italy. The influence of France in the Americas never extended to Hispanic countries; it only applied to territories that now form part of the United States or Canada. Strictly speaking, therefore, if we want to use the term “Latin” for Spanish-speaking countries, we should also call French and Italian colonies—such as Algeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or Senegal—Latin colonies, which France would rightly reject. If the criterion is linguistic heritage, then the United States and Canada should be called Teutonic America due to their linguistic origins and populations of Teutonic descent. Thus, we would have two Americas: Latin and Teutonic. Therefore, the fair and logical designation remains the universal standard: English or British America and Hispanic America, and nothing more, as the small territories of European languages in the Americas are mathematically insignificant, as the following figures indicate:

Number of speakers by language in Hispanic America (2023):

- English: 6.6 million

- French: 11.7 million

- Portuguese: 216.4 million

- Spanish: 426.5 million

Source: World Bank (2023)

Today, nearly 430 million people in Hispanic America speak Spanish. Around 216 million speak Portuguese. French and English speakers represent only 2% of the total regional population. As a result, these are Hispanic or Spanish people, not “Latinos.” Calling English-speaking America “Teutonic America” would be as accurate as calling Central and South America “Latin America.” The United States has more Germans, Swedes, Norwegians, and Dutch than there are French, Italians, or Romanians in Hispanic America.

The United States represents the Anglo-Saxon civilisation and speaks English, while south of the Rio Grande Spanish and Portuguese predominate. Therefore, there is no justification for the use of the term Latin America or its derivatives. Historical accuracy demands the rejection of these terms, and Spain—and Portugal, to a lesser extent—deserve recognition for their legacy, which should not be obscured by misleading terminology.

Regarding Spain and Portugal, they bear the responsibility for a fascinating lack of appreciation for the value and methods of self-promotion on the international stage. The most commercially minded nations attach enormous importance to this and know the value of eclipsing or suppressing the promotion of their competitors. Every time “Spanish America,” “Hispanic America,” or “Hispanic Republics” is printed or spoken, Spain’s name is rightly mentioned. In contrast, every time “Latin America” or its variants are used, the names of France and Italy are incorrectly and unjustly announced, even though neither France nor Italy played any role in the creation of these nations. Even if today no nation directly benefits from the use of the term Latin America, Spain’s legitimate recognition is constantly ignored and erased.

The use of the term Latin America lacks historical, cultural, and logical justification. The nations of Hispanic America owe their foundation, language, and civilisation to Spain and Portugal, not to any supposed Latin or Roman legacy related to France or Italy. Justice and historical truth demand that these inaccuracies be corrected and the rightful recognition of the Spanish legacy in the Americas preserved.

Adopting the term Hispanic America shifts the emphasis towards cultural pride, shared history, and the preservation of traditions that have shaped conservative thought in the region. It also underscores Spain’s role as a bridge between Europe and the Americas, positioning cultural diplomacy as a key tool to strengthen relations.

A second, more inclusive alternative is the term Ibero-America, which expands this concept to incorporate the Portuguese influence in Brazil, the largest country in the region. It highlights the Iberian Peninsula as the historical and cultural point of origin of the region’s shared identity. Ibero-America emphasises the unifying role of Iberian culture, although, as we have seen, the term Hispanic is an equally inclusive framework as it recognises contributions from both Spain and Portugal.

Beyond doing justice to the historical, cultural, and linguistic identity of the region, Hispanic America is also convenient as a term from a geopolitical perspective. This term provides a framework for Europe to position itself as a natural partner for the area, based on genuine cultural ties and a shared heritage. It also establishes a faithful connecting thread for all the countries of the American continent—except two: the United States and Canada—which would help them reach regional agreements and operate as a bloc, benefiting transatlantic dialogue with the EU.

Let this etymological excursus contribute to abandoning the imprecise terminology of Latin America, to foster greater unity within the region and greater clarity in transatlantic dialogue, emphasising the importance of cultural and spiritual ties.

I close this terminological note by recalling that in the 2024 presidential elections—in a campaign rally in Albuquerque, New Mexico—Donald J. Trump asked the audience whether they preferred to be called “Latinos” or “Hispanics.” The audience’s response was overwhelmingly in favour of the latter, confirming the thesis that Latin America is an externally imposed term and not one chosen by its own peoples. An interesting reality check from the second-largest country in the world—after Mexico—with the greatest number of Spanish speakers: the United States of America.