“I think that in time we shall deserve to have no government.”

—Jorge Luis Borges

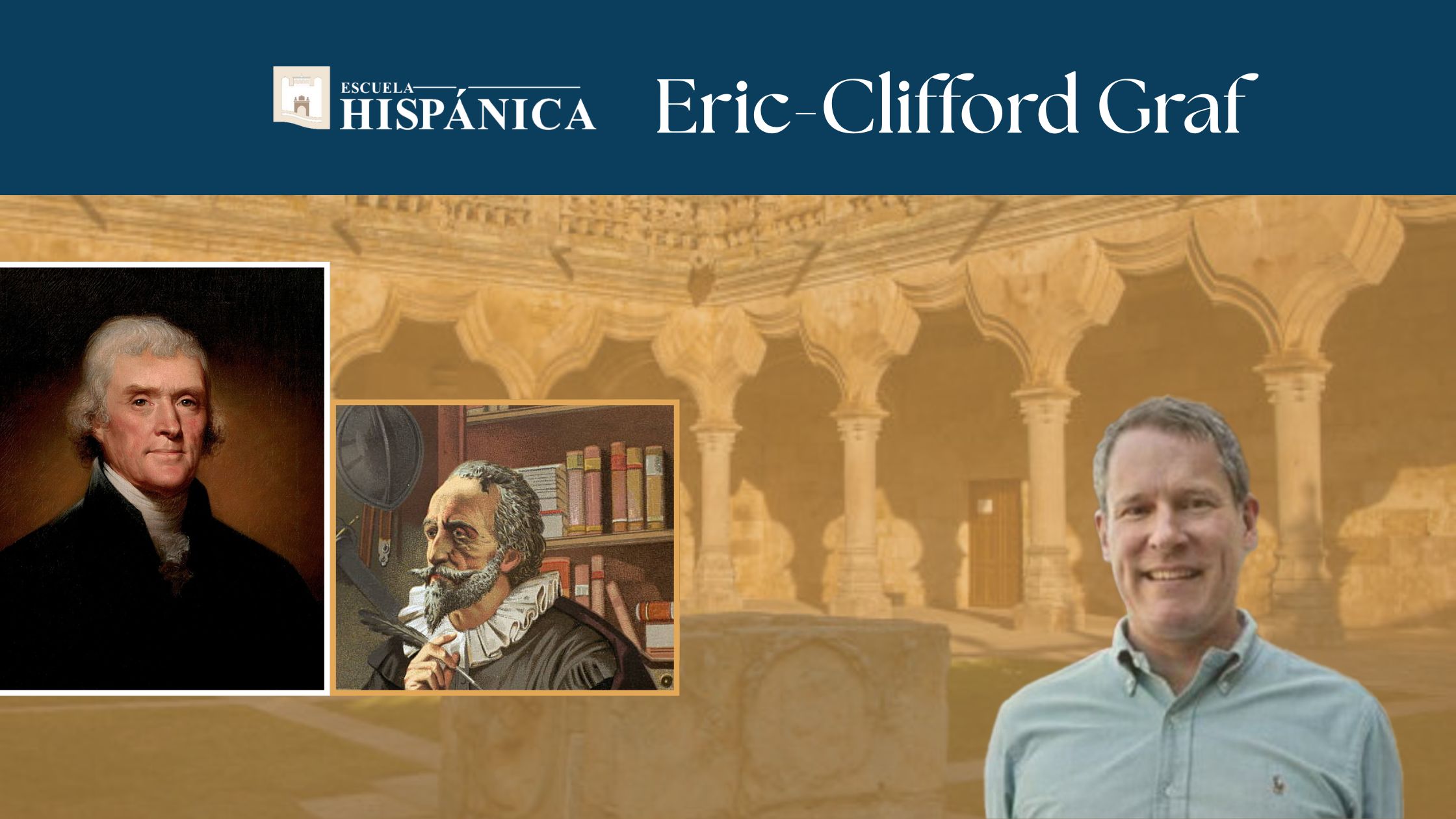

I reaffirm myself once more. Miguel de Cervantes’ novel continues to offer us the simplest and most elegant way to demonstrate the global influence of the School of Salamanca. I can only assert this because the Founder of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, was also the country’s greatest Hispanist. Enough with chauvinism: the democratic trajectory I present here is reciprocal, transatlantic, and transnational. Cervantes anticipated Jefferson’s essence, and Jefferson recognised Cervantes’ essence.

Jefferson’s aesthetic legacy—both a romantic lover and artist as well as a stateman and enlightened jurist—shows us that Cervantes’ novel was the principal inspiration for his vision of the future of the United States, a future he acknowledged as inevitably Hispanic-American. Undoubtedly, writers such as Montesquieu and Montaigne were important to him, and his closest friends were Francophiles and members of the French liberal aristocracy. But Jefferson also pointed out that Montesquieu had certain theoretical issues, and one can clearly perceive the same scepticism present in Montaigne’s essays in Cervantes’ novels. Indeed, both in his personal letters, architectural works, and Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), Jefferson’s references to the author of the first modern novel are deliberate, profound, and meaningful.

Over the last two centuries, the periodic revival and recognition of the School of Salamanca has largely been the responsibility of political scientists and economists: Carl Menger, Joseph Schumpeter, Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, and Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, among others. The blind spot in this activity has always been the history of the novel. This powerful group of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century theologians, economists, and reformist politicians—luminaries such as Vitoria, Las Casas, Azpilcueta, Molina, Mariana, Suárez, and Palafox—are indispensable for understanding how the themes and principles of multiple generations of Mediterranean Catholic thinkers influenced the Scottish Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as much as the Austrian School of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet, I contend that novelists such as Fernando de Rojas (La Celestina, c. 1499), Diego Hurtado de Mendoza (Lazarillo de Tormes, c. 1554), Miguel de Cervantes (Don Quixote, 1605/15; Novelas ejemplares, 1613), and María de Zayas (Novelas amorosas, 1637; Desengaños amorosos, 1647) will always be more useful in demonstrating the reach of these ideas.

Why insist on the utility of art over economic or political theory? Two reasons:

(1) Uncertainty. Unlike positivist economists and political scientists, liberals emphasise the importance of independent and spontaneous solutions to life’s problems over those centralised under moralists or technocrats. The novel is preferable to treatises on political economy. This organic and tragic theory of life—the basis of “negative logic,” as John Stuart Mill famously put it—is much closer to the worldview of the novel than to legislative guidance.

(2) Demographic realism. Technical geniuses’ ideas rarely convince the common masses without a creative touch. If we are to persuade the public and win the cultural battle against collectivism and victimhood, we should heed Horace’s maxim docere delectando. Producing more MBAs, political scientists, and economists is not enough. Moreover, it is a grave error to cede ground in the arts and humanities to statists and radicals. I am willing to admit that economists, historians, and entrepreneurs are smarter than others, and as a Texan, I must endorse Ortega’s observation about the error of thinking instead of acting. But no matter how preferable the pragmatic, linear mindset is, it will inevitably yield flawed outcomes from time to time. In the U.S., for example, the pinnacle of technical education is MIT, yet predictably, more than comparable universities, it promotes neo-racism in demographic quotas among students and faculty. Setting aside intelligence, the cold logic of the left hemisphere of the brain requires the creativity of law to impose moral limits.

In Cervantes’ narrative work, one reads a long series of casuistic reflections on moral, political, and economic themes, echoing the jurists of the Renaissance School of Salamanca while anticipating the principles of classical liberalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A few examples: trade can resolve international conflicts (La española inglesa), race should not impact the politics of a modern republic (El coloquio de los perros), and material value is often intimately subjective (Don Quixote). To these traits of the Cervantine novel we add the essentially bicultural reality of the Western Hemisphere: the Hispanic world is the main ethnic and cultural frontier of the U.S., so it is inevitable that the 900 million Spanish-speakers in Latin America converge with the 350 million English-speakers north of the Rio Grande. It should not surprise us that Jefferson was the first and greatest Hispanist and Cervantist in the United States.

By 1787, Jefferson’s growing library of Spanish texts included Antonio de Ulloa, Francisco López de Gómara, Jorge Juan y Santacilia, Antonio de Solís y Rivadeneyra, and Gabriel de Cárdenas y Cano, among others he intended to acquire. We must also add Juan de Mariana, whose History of Spain Jefferson sent to his best friend James Madison, and of course Cervantes, particularly Don Quixote and Novelas ejemplares, which profoundly influenced the Founder of American democracy. I admit my bias: I am a Jeffersonian. If I had to recommend three authors for Americans to read in preparation for the Hispanic-American future, they would be Mariana, Cervantes, and Borges. For those seeking points of contact between Anglo and Hispanic worlds, there they are.

Jefferson’s letters are full of references to Don Quixote (eleven in total, plus eight letters on the topic from family and acquaintances). It may have been his favourite literary work. Sometimes the reference is metaphorical, though politically significant—for example, his 19 July 1822 letter to Benjamin Waterhouse, where he alludes to the First Amendment:

“Don Quixote undertook to repair the corporeal errors of the world, but the repair of mental caprices would be a task more than quixotic. I would attempt to bring sound understanding to the mad skulls of Bedlam before trying to instil reason in that of an Athanasian.”

Other cases clearly aim to establish an intellectual foundation for his nation and family. Jefferson’s first letter referring to Cervantes’ novel was 3 August 1771 to Robert Shipwith, recommending the unfortunate translation by Tobias Smollet. Later, his important letter to Mons. de Marbois (who inspired his Notes on the State of Virginia), dated 5 December 1783, thanks the marquis for recommending books for his daughter Martha’s education and mentions leaving her copies of Gil Blas and Don Quixote, which he considered “among the best books of their kind.”

We must also emphasise letters between Jefferson and his daughter Mary in 1790–91, discussing her promise to read the first modern novel. From this, it is clear Jefferson considered Cervantes essential reading for his daughter, perhaps as a means of communicating moral alignment. Jefferson’s daughters opposed slavery; Martha, in a 3 May 1787 letter, wrote:

“I wish with all my soul that all poor Negroes be freed. My heart grieves when I think that these our fellow beings are treated so terribly by many of our countrymen.”

Jefferson’s architecture also reveals Cervantine influence. Two cases stand out: the Rotunda at the University of Virginia, completed shortly after his death in 1826, and his home at Monticello, mostly finished by 1809, though he continued minor modifications until his death. The Rotunda explicitly appropriates both the Pantheon of Rome and Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. It is difficult to imagine Jefferson was unfamiliar with the iconic figure, either through prints or Alberti’s De pictura. He also owned a replica of da Vinci’s San Giovanni Battista and a sixteenth-century edition of Alberti’s L’architettura.

Jefferson’s visit to Buckingham House in 1786, near George III’s da Vinci notebooks, hints that the “architect of democracy” (as Borges called him) saw the Vitruvian Man as symbolising the individual’s struggle against sovereign power. Monticello itself reflects Cervantes’ metaphorical labyrinth of Sierra Morena, evident in the statue of Ariadne/Cleopatra, the bull head motif, and the asymmetrical imperial style, symbolising European-African cultural fusion. After returning from France in 1789, Jefferson oriented Monticello west, toward New Spain—from Louisiana to California—marking it as a Mediterranean-Hispanic solution to the racial question of the new republic.

Finally, Question VI of the Notes on the State of Virginia, a sine qua non of American democracy, contains the most impressive allusion to Cervantes by an American author I have ever read. Jefferson’s references to Aesop (source of the famous Latin maxim in Don Quixote’s prologue) and Ariosto (Cervantes’ favourite modern writer) show that he closely followed the inventor of the novel. In Question VI, Jefferson refers to eight major Western literary figures: Shakespeare, Milton, Tasso, Racine, Voltaire, Camões, Homer, and Virgil. He notes that Homer and Virgil are distinguished by their universal reach—their imperial epics transcending language and nation. A few pages earlier, he ironically contrasts Aesop and Ariosto, emphasising racial miscegenation as a solution to slavery.

Cervantes’ famous Latin maxim, “Non bene pro toto libertas venditur auro” (Liberty is not sold well for all the gold), sets the stage for the novel’s treatment of race

and slavery. Similarly, in El coloquio de los perros, Jefferson’s library included this work, reinforcing his understanding of Cervantes’ moral vision. In chapter 26 of Don Quixote, Ariosto is referenced, coinciding with Don Quixote’s reflections on interracial relations—underscoring Jefferson’s deep engagement with Cervantes.

Recent essays, short stories, and interviews by Borges, alongside Annette Gordon-Reed’s thesis on Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings, reveal that Jefferson’s multiple allusions to Cervantes indicate his belief that solving America’s racial labyrinth required engaging with the Hispanic world. The Mediterranean, Caribbean, and Latin American worlds model miscegenation, offering the proper perspective to address one of the most destructive fixations of American culture.

Nick Szabo, alleged inventor of Bitcoin, once said at Francisco Marroquín University that if your good idea is not believed, you should doubt it. Jefferson’s approach in Question VI mirrors this “negative logic”: recognise the possibility of error, reassess premises and biases, but if the idea persists, it may be others who are wrong. Jefferson’s constitutionalism sought wisdom in Spain, not France. Cervantes’ weight in the Notes on the State of Virginia is greater than most American scholars realise. Jeffersonian democracy consists of learning from the past and looking to the future, meaning Cervantes and the moralists, politicians, and economists of Salamanca remain the most urgent sources to uncover.

The sad irony is that neither culture pays attention to these intersections, even when opportunities abound. In Florida—where Miami’s population is three-quarters Hispanic—pseudo-liberal conservatives are poised to implement the first university reform in the U.S. in over fifty years, following a Baptist Michigan model. Meanwhile, the latest Spanish editor of the Notes has expurgated an entire chapter of Jefferson’s magnum opus.

If we can imagine a Hispanic-American future with great socio-economic, scientific, and cultural potential, Jefferson’s multiple allusions to Cervantes across his letters, architecture, and Notes on the State of Virginia contain something beautiful. Americans often think Jefferson was Francophile, but Spain and Rome were also key references. His 1787 French tour, extending into northern Italy, reflects his admiration for the Mediterranean world as a model for the democratic empire he was designing.

Today, most U.S. universities—and especially elite institutions such as Harvard, MIT, Princeton, Stanford, Rice, and Chicago—persist in privileging French as the language of philosophical and cultural knowledge. Sociology, politics, and literature remain dominated by French study. I side with Jefferson, both intellectually and aesthetically. It is time to replace this outdated Francophile fantasy with the study of Spanish—not just pragmatically, but for its philosophical, historical, and cultural value. Spanish is integral to our present and future in the Atlantic world, and the great works of Cervantes, Jefferson, and Borges can help realise this academic shift. Success would enhance both the study of the School of Salamanca and the principles of classical liberalism, benefiting the world for centuries to come.

—Eric-Clifford Graf

Works Cited:

- Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quijote de la Mancha. Ed. Francisco Rico. Barcelona: Crítica, 1998.

- Graf, Eric-Clifford. Anatomy of Liberty in Don Quijote de la Mancha. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021.

- Herrero, Javier. “Sierra Morena as Labyrinth: From Wildness to Christian Knighthood.” Critical Essays on Cervantes. Ed. Ruth El Saffar. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986. 67–80.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Writings. New York: Library of America, 2011.

- Escritos políticos. Ed. Antonio Escohotado. Madrid: Tecnos, 2014.

- Liggio, Leonard P. 1990. “The Hispanic Tradition of Liberty: The Road Not Taken in Latin America.” Lecture, Mont Pelerin Society Regional Meeting, 12 Jan. 1990, Antigua, Guatemala.