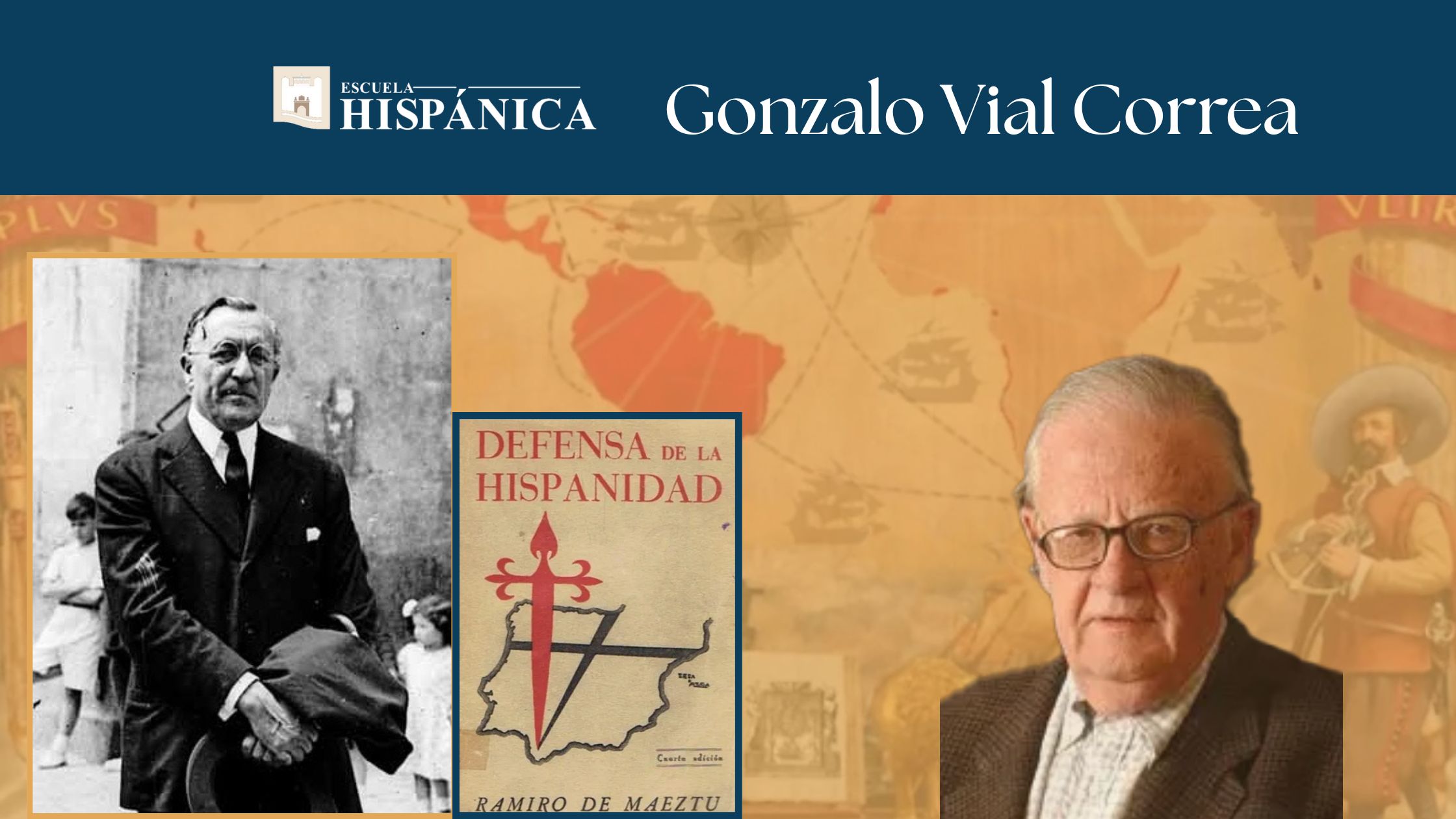

Next year will mark a century since the birth of Ramiro de Maeztu.

Maeztu, murdered in Madrid during the Civil War in 1936, was a notable Basque writer, some of whose essays—such as the analysis and comparison of Don Juan, Don Quixote, and La Celestina—have become classics of twentieth-century Spanish literature.

Following a nearly unbroken line of great Basques—from Saint Ignatius to Unamuno—Maeztu, without losing his deep affection for his native region, also identified spiritually with the larger homeland. Like Don Miguel, “Spain pained him.” From there, he ascended to an even broader plane: that of Hispanidad.

By this, Maeztu meant the community of peoples who had received from Spain its way of conceiving life—that is, a tradition of values.

For the Basque writer, Spain had constructed an “imago mundi”, feeling passionately the need to unite faith and works. “Faith without works is dead faith,” had been written precisely by Santiago, the Apostle of Spain. Across the centuries, Spaniards would continually echo this assertion. Until the great sixteenth-century debate on the corresponding value of faith and works—the Reformation broke Christendom. Maeztu pointed out that at that time it was a Spanish theologian, Diego Laínez, who was the most ardent defender of the importance of works for salvation. Laínez’s intervention in this regard, at the Council of Trent, Maeztu argued, sealed the clear doctrinal difference with the Protestants on this fundamental matter… a difference that other, more diplomatic conciliar fathers would have preferred to minimise.

Such a strong valuation of works—Maeztu later noted—combined with other ideas of Christian origin, leads directly to the affirmation of the essential equality and permanent solidarity of humankind, of all men, regardless of race, nationality or social status… “the unity of the flowers in the body of Christ,” in the words of another Spaniard of this century, the poet Rosales.

And as, through logical progression that is also hard to dispute, the equality of men implies that each individual possesses a treasure of attributes unique to them, which no other person has the right to violate, the Hispanic peoples—before the Anglo-Saxons and on a completely different ideological basis—developed the theory and system of personal liberties, which guarantee the preservation of those attributes.

Such liberties must also be respected by authority. The subjection of authority—and of all—to the law, that is, the rule of law, likewise forms part of this Hispanic “imago mundi”, expressed in the maxim that runs from Saint Isidore of Seville to the Golden Age theatre, through the Partidas: “You shall be king if you do right, and if you do not do right, you shall not be king.”

In a later stage of maturation, thinkers such as Suárez and Vitoria extended these concepts from the world of individuals to that of nations. The notion of an international community governed by ethical norms thus became part of the Hispanic heritage.

Maeztu poured these and other ideas into an essay, “Defensa de la Hispanidad”, which achieved immediate success throughout Spanish-speaking countries.

Since then, the word—Hispanidad—has become commonplace and, like any currency, prone to falsifications.

The number of misconceptions surrounding it is astonishing.

At the outset, Hispanidad is often confused with admiration or affection for all things Spanish—that is, with “hispanismo”. Hispanists, in this sense, might be Hemingway, Bizet, Rodríguez Larreta or—even at a more rudimentary level—the tourist who enjoys bullfighting, flamenco, or the sun on the beaches of Torremolinos. But such Hispanists may (and often do) have nothing to do with Hispanidad.

Hence Jaime Eyzaguirre—who recognised and respected Maeztu’s spiritual heritage—added that he was not a Hispanist, but a “Hispano”. “Being a Hispanist is the attitude of an outsider who admires Iberian culture from afar. Being Hispanic, for the Chilean, is a matter of belonging, not servile imitation.”

It is also common to equate Hispanidad with adherence—or at least sympathy—to certain regimes, ideologies, or political figures. For instance, some time ago, Le Monde reported that in Chile Hispanidad had been a “substitute for fascism.” It is true that the person making such an assertion was a Belgian sociologist from the era of the Unidad Popular, whose work combined frivolity, bold ignorance, and obscure pedantry. Nevertheless, the mere fact that such absurdities could appear in a world-famous newspaper without ridicule demonstrates the confusion between Hispanidad and specific political doctrines or loyalties.

No, they are unrelated. One can be monarchist or republican, Francoist or anti-Francoist, and still share the “imago mundi” of Hispanidad.

However, it is impossible to be totalitarian—whether Marxist-Leninist or other purely Hegelian totalitarianisms—and adhere to Hispanidad. These totalitarianisms possess their own “imago mundi”, radically anti-Christian. And we have already seen that the essence of Hispanidad lies in tradition and the accentuation of certain basic Christian ideas.

There are also those who perceive Hispanidad as an ethnic or even racist element. There is none. It is a spiritual tradition: people of any race can embrace it. Moreover, racial egalitarianism—as noted above—is one of the key elements of this tradition. This egalitarianism has been embodied in the Hispanic mestizaje across all continents. Maeztu, with remarkable foresight, included the Lusophone world—Portugal and Brazil—highlighting that Hispanidad, like its inspiration Christ, in the words of our colonial Bishop Villarroel, “makes no distinction of colours and values equally the good works of a black slave and a white king.”

Finally, another mistaken idea is that Spain, as a concrete country, constitutes a “leading head” or “first among equals” of Hispanidad.

It is true that Spain earned that position in the past through its discovery, colonisation, evangelisation, and cultural work in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, and by having created, transmitted, and spread the imago mundi of Hispanidad.

But maintaining—or, if you will, reclaiming—that position depends precisely on works. If Spain embraces and updates the eternal ideas of Hispanidad today, it will be the head of the spiritual community. If its ruling classes prefer to chase Mammon, and its intellectuals poison themselves with the remnants of outdated neo-Marxism and intoxicate themselves with the fruitless horrors of violence, then Spain may be many things, but it will not lead Hispanidad.

“My works, not my ancestors, will lead me to heaven,” says an old Spanish proverb often cited by Jaime Eyzaguirre. It applies both to individuals and to nations.

In any case, with or without Spain, Hispanidad will endure.

Will it endure? Does it live today? What is its future?

Because Hispanidad is a spiritual reality, its ideals may sometimes seem ghostly, either in themselves or in relation to the nations that share them. We— or at least we believe ourselves—so insignificant among the peoples of Hispanidad, that at our lowest moments, it appears very small indeed.

Yet if we look back to the historical moment when Maeztu’s “Defensa de la Hispanidad” appeared, we see the remarkable strength of this imago mundi.

It was the 1930s—the perhaps most lamentable decade in the history of the Hispanic peoples.

In Spain itself, the wound of 1898 was still open. A sterile monarchy had collapsed; a shapeless or premature Republic had not yet fully formed… nor would it ever. Hatred, political passions, backwardness, and misery prevailed.

And what of the Hispanic American peoples? Their universal voice was nil; they seemed immobilised—for all eternity—by their own indolence and by the “golden and steel nail” of the Yankee, as Gabriela Mistral called it.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world appeared full of vitality and promise… which were the absolute negation of the imago mundi of Hispanidad. The U.S.—already past the Great Depression—proclaimed the incessant and growing successes of a society based on the drive for money. In distant Russia, the communists told us, the kindly Father Stalin was hastily forging a happy utopia in which “bourgeois freedom” was suppressed as unnecessary. Without it, and without equality—sacrificed to the concept of a superior race—the Central European totalitarianisms devoured nations, raised invincible armies, and also reached peaks of wealth and prosperity.

And the supreme paradox: all these works were carried out by those who directly or indirectly came from those who had denied the efficacy of works for salvation, defenders of dead faith! Meanwhile, we, heirs of the champions of living faith, of salvific works, lay in backwardness and inaction…

Nearly half a century has passed. Paraphrasing the famous coplista, we may ask:

What became of the confident Yankee optimism? “The American way of life,” the happy “homeland of universal socialism,” the Nazi millennium, the New Rome of fascism and its “mare nostrum””… what became of them?

By contrast, many ideals of Hispanidad—racial equality, the community of nations based on that equality, the primacy of national and personal freedom—are gaining extraordinary strength today and mobilise, sometimes clearly, sometimes ambiguously, peoples around the world.

And—very importantly, though with its dangers—the Hispanic peoples are gradually but decisively setting themselves in motion; emerging from Eastern immobility; eliminating the mysterious contradiction—their worst characteristic—between affirmation of living faith and temporal backwardness; doing their own works without forgetting (hopefully) that without faith, works alone do not save.

The examples of Spain and Brazil—the most notable, but not the only ones—immediately come to mind. Would anyone have suspected in

The 1930s that, by the 1950s, Spain would become the world’s leading tourist power; that it would organise itself to delight and serve millions of annual visitors to perfection; that it would grow with a momentum equal or superior to the rest of Europe; that it would have an expansive and aggressive international trade; that it would export capital, advanced technology, and tens of thousands of automobiles?

Ultimately, the future of Hispanidad lies here: in material progress, but within a tradition of values and proven justice; in practising—and teaching others—the old and difficult Christian science of living and creating in the world, but not for the world, of reconciling the temporal reality we face with the eternal reality we await.